DAKAR, Senegal, June 13, 2024/ — Dr Olakounlé Gilles Yabi, Founder and CEO of the citizen think tank WATHI (www.WATHI.org).

In 2014, when I was working to launch the citizen think tank WATHI, I wrote the following in the concept note I proposed to dozens of friends interested in the present and future of West Africa:

‘West Africa is a very young region. The proportion of the population aged under 25 in each country of the region exceeds 60%. Demographic growth in West Africa will remain strong in the medium term. The prospects outlined by the region demographic projections entail daunting security, economic and social challenges for countries whose states and economies are mostly weak. These demographic trends, together with the region’s abundant natural resources and the weakness of local production systems, are some of the reasons behind the renewed interest in African economies shown by old and new dominant players in the global economy. However, if the enthusiasm regarding West Africa’s economic promise is not tempered by an overall acknowledgment of the security and political threats the region is facing, the result will likely be further disillusionment’.

One of the worst scenarios we could have imagined ten years ago

Ten years after this diagnosis of the state of the region, the situation in West Africa in 2024 looks grimly like one of the worst-case scenarios we could have imagined back then. I’m among those who believe that we need to change the narrative about our part of the world, about Africa in general.

However, the desire to highlight the positive developments in many areas, the extraordinary potential of our young people, should not distract us from a dispassionate observation of the reality of the moment. The only way we will be able to bring about the much-needed changes in political practices in the region is through a candid observation of the state of affairs in the region.

West Africa is currently facing unprecedented level of security and political uncertainty. Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and Nigeria are among the 10 countries most affected by terrorism in the world. This however is only a partial reflection of the spread of insecurity, the rivialization of violence and the overall worrisome consequences on social cohesion and the physical and mental health of millions of children who are growing up in a context of violence and without any educational or emotional support from their families.

In four countries undergoing transition following coups d’état (Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea and Niger), there is no regional institutional framework to set limits on military rulers who have no internal checks and balances. However, the restrictions on political freedoms and freedom of expression by those regimes, against a backdrop of growing economic difficulties for the population, are beginning to provoke protests and strikes, despite the high risks of repression and threat of imprisonment.

In some other West African countries that are formally democratic and run by civilians, checks and balances exist only in theory, and in reality, there is little possibility of political alternation. In many countries presidents have taken the initiative to revise or change the constitution to evade term limit and remain in power indefinitely.

The recent constitutional reform in Togo, a country that has not had a democratic transition for 57 years, provided another shocking example of a parody of democracy in West Africa. The content of the country’s supreme law, which abolishes presidential elections by universal suffrage, was not made public until after its enactment.

And even in the few countries that are often held up as examples of political alternation through credible elections, with the possible exception of Cabo Verde, the general perception held by citizens is that resources and economic opportunities are monopolised by small circles of relatives, friends and political allies. Democracy and elections continue to unbearably accommodate high levels of corruption, mismanagement and embezzlement.

An unprecedented crisis in regional integration

The simultaneous announcement on 28 January 2024 by the governments in power in Bamako, Ouagadougou and Niamey to leave ECOWAS opened up an unprecedented crisis in the process of regional integration in West Africa. We have all become witness to the continued strained relationship between neighboring countries such as Benin and Niger, a distressing waste of time and energy at a moment when communities continue to be impoverished by restrictions on cross-border economic activities.

The next few months will be decisive for the regional integration process. The decision of Burkina, Mali and Niger to leave ECOWAS enable military leaders in those three countries to free themselves from ECOWAS supervision of transition and related constraints.

They were also able to make this announcement because they knew that the short-term political and economic cost would be limited. As a matter of fact, they did not withdraw from the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), which brings together eight countries that share a common currency, the CFA franc (seven countries that were once colonies of France and have been joined by Guinea Bissau in 1997).

Membership of WAEMU allows these countries to retain most of the benefits of regional integration within this sub-area of ECOWAS. In addition, leaving WAEMU is more difficult and requires prior preparations than exiting ECOWAS.

The political cost of leaving ECOWAS was also limited because the military leaders were aware of the degraded image of the regional organisation among a large part of West African population, not only in the Sahel. ECOWAS’ management of the coup d’état in Niger dealt a blow to the regional organization’s perception among West African public opinion.

The political and symbolic impact offered an unhoped-for opportunity for the military leaders to portray themselves as the victims of a plot by their own regional organisation to launch a military intervention in one of its own member states.

A regional organisation always reflects the political will, capacities and dynamics of its member states

Many West Africans reduce ECOWAS to the Conference of Heads of State and Government, which takes decisions on political and security issues at ordinary and extraordinary summits. All the other dimensions of integration that are the subject of the daily work of the Commission, other bodies and specialised agencies, are simply not known or poorly known.

The vast majority of young people in urban and rural areas have no precise knowledge of the history of regional integration, of the major stages in the construction of ECOWAS since 1975, of the benefits of regional integration for the people, of ECOWAS’s decisive diplomatic and military interventions in countries in armed conflict in the 1990s and 2000s.

Few citizens of West African countries can mention the names and missions of ECOWAS’s two specialised agencies. Few are aware of the existence and crucial role of the Court of Justice, which can be seized by any citizen of a member country even before domestic remedies have been exhausted.

This court is a great tool for the promotion and protection of human rights in West Africa. However, it has consistently been undermined by the same member states which created it and who often do not abide by its rulings. The region is therefore paying the price for what has not been done in terms of education, the inclusion of regional integration issues in curricula and overall communication on regional integration.

There is a great deal of confusion between what is the responsibility of the Member States and what is that of ECOWAS. Many people are fiercely critical of ECOWAS because they expect it to be a substitute for states, a means of freeing themselves from their weaknesses, their dysfunctions and sometimes the lack of legitimacy of their leaders.

It is not ECOWAS that chooses the Heads of State of the member countries, but the latter then form the college of ultimate political decision-makers of the organisation.

This is true of all regional organisations worldwide. Regional organisations cannot work miracles in the absence of impetus, strong will and capacity for action on the part of the member countries, or at least a core group of influential countries among them.

A regional organisation always depends on its member states, which can give or refrain from giving the organisation the means to act and the freedom it needs to implement its integration agenda.

It must be acknowledged that some very unfortunate decisions have been taken by the ECOWAS Conference of Heads of State and Government in recent years. It is also necessary to recognise the structural shortcomings, while welcoming the many achievements of ECOWAS over the past 49 years and the immensity of the ground covered.

If the record had been better in terms of regional infrastructure, for example if ECOWAS had been able to lead and ensure the effective implementation of a regional rail network programme, if the record had been better in terms of the harmonisation of sectoral policies and the promotion of regional integration in education systems, the political cost to each Member State of leaving the Community would have been much higher. And that rubicon would have been much harder to cross even for authorities who have seized power by force.

What is at stake is the West Africa we want for our children

Alongside discreet diplomatic efforts, a public campaign is needed to explain why ECOWAS is an essential, crucial institution for the future of West Africa. The ECOWAS Commission must speak directly to the people. The organisation should explain the raison d’être of the additional protocol on democracy and good governance. It should also explain the reasoning behind the broadening over the years of its missions and objectives, beyond economic integration.

Those who criticise ECOWAS for straying from its original economic mission, for violating the sovereignty of states by interfering in internal political issues, are either ignoring the rational evolution of the organisation’s rules and regulations in responding to armed conflicts and violent political crises, or are acting in bad faith.

We must, however, accept a debate with all these voices acting in good faith or not. We need to explain how the promotion of the rule of law in the region is not just a dream of westernised elites who are out of touch with reality, and how it is the only way to protect all citizens of West African countries from arbitrariness.

More than ever, West Africa needs a strong ECOWAS that focuses on clear priorities. We need an ECOWAS that develops its capacity for strategic thinking by capitalising on the region’s human resources, including the diaspora.

We need an ECOWAS that helps to protect the region from the potentially devastating consequences of battles for influence between powers on West African soil. As we all know, without perhaps realising the magnitude of the threat, this battle is also being waged in cyberspace, where opinions and certainties are spouted all day long via social media, in order to suppress any hindsight, critical thinking or attachment to facts in people’s minds.

We need an ECOWAS that gives young people reasons to dream. We need to create and maintain a desire for integration. We also need the demographic, economic and military powerhouse of the region to act as a driving force.

We need a committed Nigeria and a core of personalities in each of the countries in the region who are genuinely committed to the integration project. Let me reiterate: no regional organisation exists without its member countries and without the social, political, economic and cultural forces that shape the development of each of these countries.

What will be at stake in the coming months is the shape and the type of West African region we want for our youth, our children for decades to come. The choice before us is that of continuing belief in the possibility of making West Africa a region of collective progress and freedom, where fundamental rights are protected or resignation.

The latter is undesirable because it implies accepting that our region is deeply fragmented, that each country becomes inward looking and focuses on what it perceives as its strictly national interests. It would mean accepting the real and very high risk of a return, almost everywhere, to autocratic regimes where leaders are accountable to no one.

We have already experienced this in the past in a majority of countries in the region and on the African continent. It was not a resounding success. Resignation is therefore not an option.

This article is a modified and expanded version of Gilles Yabi’s speech at a public event organised by the ECOWAS observation mission at the United Nations to mark the regional organisation’s 49th anniversary, New York, 7 June 2024.

Distributed by APO Group on behalf of West Africa Think Tank (WATHI).

For media enquiries:

Please contact:

Ms Hadidjette Kangouline

Communication Officer

hadji.kangouline@wathi.org

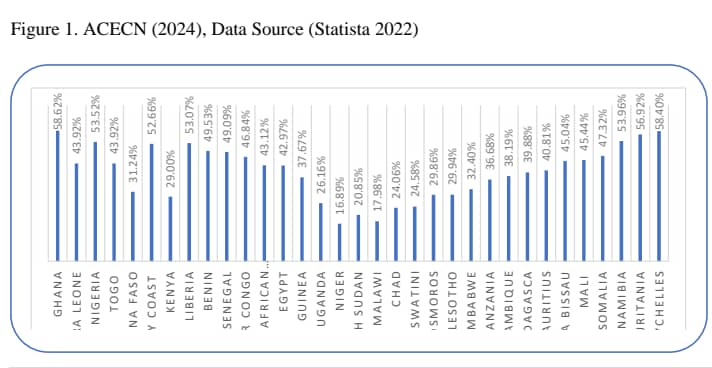

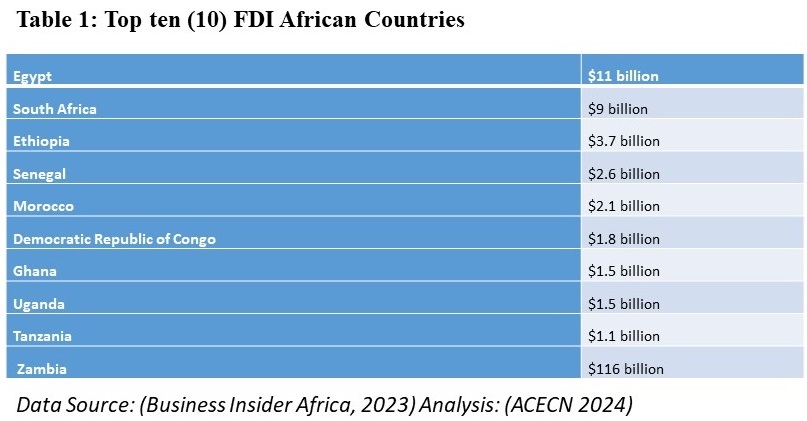

Real estate investment in Ghana has become an increasingly attractive option for investors looking to diversify their portfolios and tap into the country’s promising real estate industry, the country with a stable political environment, a young and rapidly urbanizing population, and rising incomes, Ghana’s real estate sector presents exciting opportunities in all categories of real estate, the residential, commercial, and industrial properties. This is a series brought to you by the Africa Continental Engineering & Construction Network Ltd (

Real estate investment in Ghana has become an increasingly attractive option for investors looking to diversify their portfolios and tap into the country’s promising real estate industry, the country with a stable political environment, a young and rapidly urbanizing population, and rising incomes, Ghana’s real estate sector presents exciting opportunities in all categories of real estate, the residential, commercial, and industrial properties. This is a series brought to you by the Africa Continental Engineering & Construction Network Ltd (