Author: Stephanie

PhD Candidate, University di Bologna

First Published: February 27, 2024 4.08pm SAST

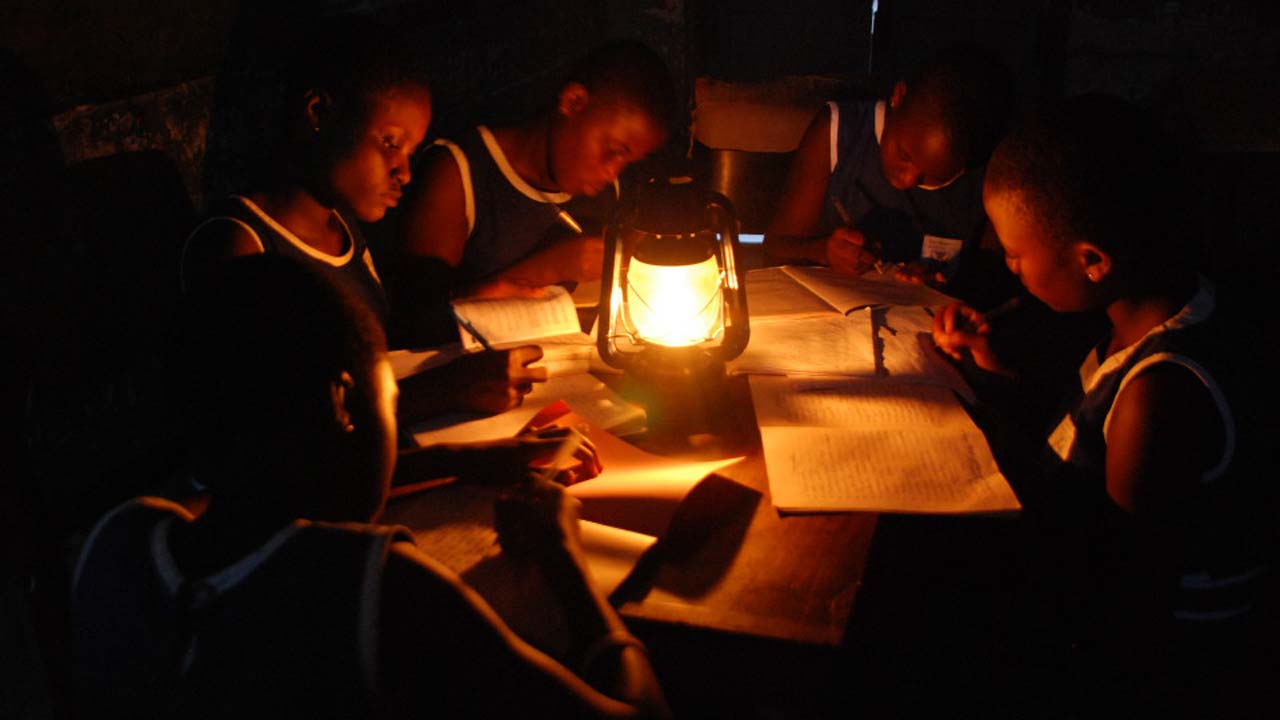

Digital technologies have many potential benefits for people in African countries. They can support the delivery of healthcare services, promote access to education and lifelong learning, and enhance financial inclusion.

But there are obstacles to realizing these benefits. The backbone infrastructure needed to connect communities is missing in places. Technology and finance are lacking too.

In 2023, only 83% of the population of sub-Saharan Africa was covered by at least a 3G mobile network. In all other regions the coverage was more than 95%.

In the same year, less than half of Africa’s population had an active mobile broadband subscription, lagging behind Arab states (75%) and the Asia-Pacific region (88%).

Therefore, Africans made up a substantial share of the estimated 2.6 billion people globally who remained offline in 2023.

A key partner in Africa in unclogging this bottleneck is China. Several African countries depend on China as their main technology provider and sponsor of large digital infrastructural projects.

This relationship is the subject of a study I published recently. The study showed that at least 38 countries worked closely with Chinese companies to advance their domestic fibre-optic network and data centre infrastructure or their technological know-how.

China’s involvement was critical as African countries made great strides in digital development. Despite the persisting digital divide between Africa and other regions, 3G network coverage increased from 22% to 83% between 2010 and 2023. Active mobile broadband subscriptions increased from less than 2% in 2010 to 48% in 2023.

For governments, however, there is a risk that foreign-driven digital development will keep existing dependence structures in place.

Reasons for dependence on foreign technology and finance

The global market for information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure is controlled by a handful of producers. For instance, the main suppliers of fibre-optic cables, a network component that enables high-speed internet, are China-based Huawei and ZTE and the Swedish company Ericsson.

Many African countries, with limited internal revenues, can’t afford these network components. Infrastructure investments depend on foreign finance, including concessional loans, commercial credits, or public-private partnerships. These may also influence a state’s choice of infrastructure provider.

The African continent’s terrain adds to the technological and financial difficulties. Vast lands and challenging topographies make the roll-out of infrastructure very expensive. Private investors avoid sparsely populated areas because it doesn’t pay them to deliver a service there.

Landlocked states depend on the infrastructure and goodwill of coastal countries to connect to international fibre-optic landing stations.

A full-package solution

It is sometimes assumed that African leaders choose Chinese providers because they offer the cheapest technology. Anecdotal evidence suggests otherwise. Chinese contractors are attractive partners because they can offer full-package solutions that include finance.

Under the so-called “EPC+F” (Engineer, Procure, Construct + Fund/Finance) scheme, Chinese companies like Huawei and ZTE oversee the engineering, procurement and construction while Chinese banks provide state-backed finance. Angola, Uganda and Zambia are just some of the countries which seem to have benefited from this type of deal.

All-round solutions like this appeal to African countries.

What is in it for China?

As part of its “go-global” strategy, the Chinese government encourages Chinese companies to invest and operate overseas. The government offers financial backing and expects companies to raise the global competitiveness of Chinese products and the national economy.

In the long term, Beijing seeks to establish and promote Chinese digital standards and norms. Research partnerships and training opportunities expose a growing number of students to Chinese technology.

The Chinese government’s expectation is that mobile applications and startups in Africa will increasingly reflect Beijing’s technological and ideological principles. That includes China’s interpretation of human rights, data privacy and freedom of speech.

This aligns with the vision of China’s “Digital Silk Road”, which complements its Belt and Road Initiative, creating new trade routes.

In the digital realm, the goal is technological primacy and greater autonomy from western suppliers. The government is striving for a more Sino-centric global digital order. Infrastructure investments and training partnerships in African countries offer a starting point.

Long-term implications

From a technological perspective, over-reliance on a single infrastructure supplier makes the client state more vulnerable. When a customer depends heavily on a particular supplier, it’s difficult and costly to switch to a different provider. African countries could become locked into the Chinese digital ecosystem.

Researchers like Arthur Gwagwa from the Ethics Institute at Utrecht University (Netherlands) believe that China’s export of critical infrastructure components will enable military and industrial espionage. These claims assert that Chinese-made equipment is designed in a way that could facilitate cyber-attacks.

Human Rights Watch, an international NGO that conducts research and advocacy on human rights, has raised concerns that Chinese infrastructure increases the risk of technology-enabled authoritarianism.

In particular, Huawei has been accused of colluding with governments to spy on political opponents in Uganda and Zambia. Huawei has denied the allegations.

The way forward

Chinese involvement provides a rapid path to digital progress for African nations. It also exposes African states to the risk of long-term dependence. The remedy is to diversify infrastructure supply, training opportunities and partnerships.

There is also a need to call for interoperability in international forums such as the International Telecommunications Union, a UN agency responsible for issues related to information and communication technologies.

Interoperability allows a product or system to interact with other products and systems. It means clients can buy technological components from different providers and switch to other technological solutions. It favours market competition and higher quality solutions by preventing users from being locked in to one vendor.

Finally, in the long term African countries should produce their own infrastructure and become less dependent.

SOURCE

The Conversation